I recently traveled to Japan to teach a programming workshop and to spend some time traveling for fun. Despite being between academic terms, I worried about how the two weeks might affect my productivity and that of the lab in my absence. Often when I travel, I can carve out time to respond to a few emails or take some Zoom calls. However, on this trip, the time difference of 14 hours forced me not to juggle multiple responsibilities. I had to focus on being in Japan. In other words, I was forced to say no. I was forced to not participate in meetings. I was forced not respond to emails quickly. I was forced to decline manuscript reviews.

Why did I have to travel nearly 7,000 miles to say no?

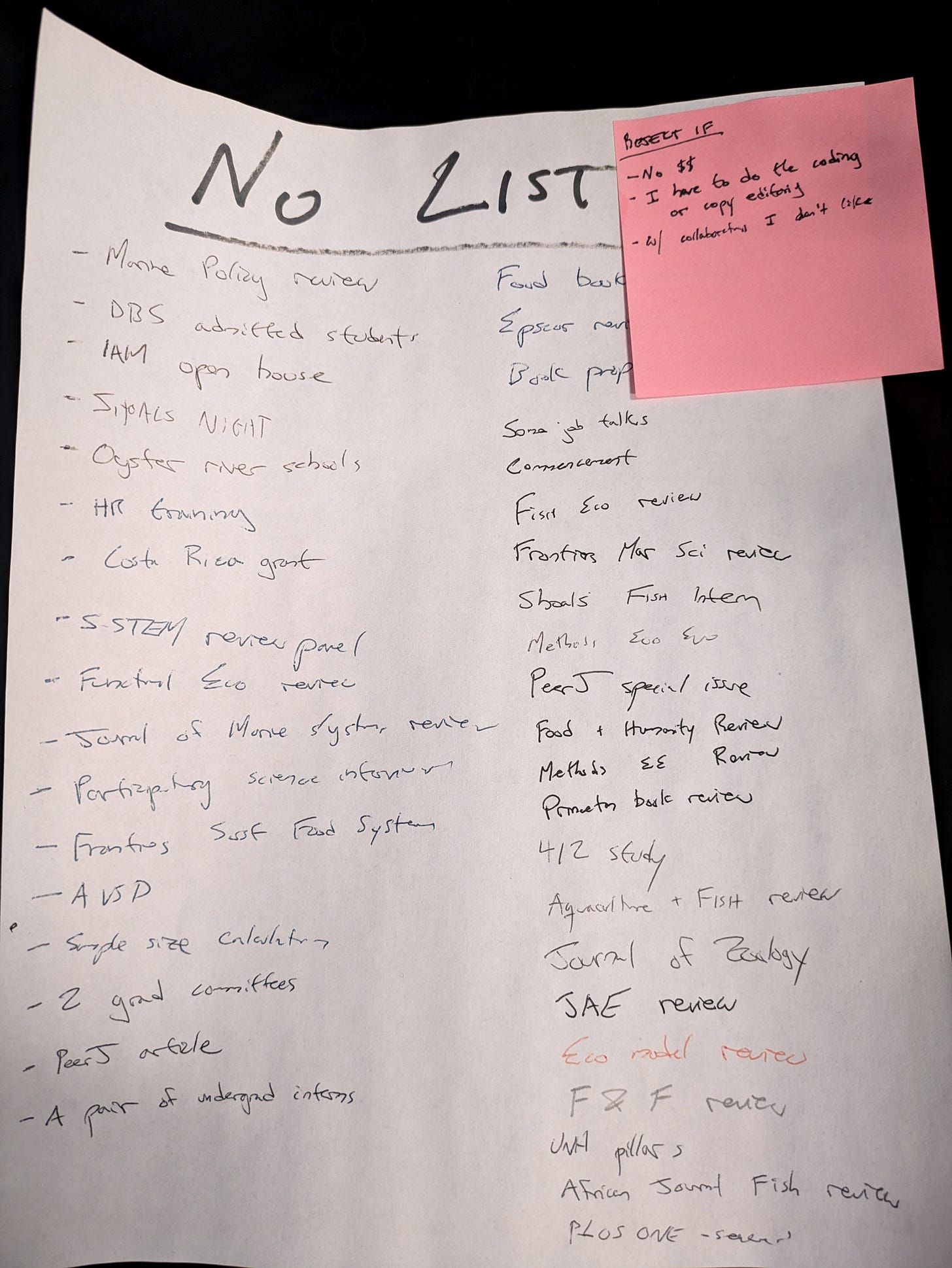

Although I didn’t give it much thought in advance of the trip, my time in Japan came at an important time in my life. In 2024, I crafted my first “no” list (see below). I took a blank piece of paper (actually the back of a scantron) and started listing every request I declined. I hung the sheet next to my desk. The list was my attempt to say no to more things in my professional life and to document it. I ended up writing down 39 items. I was surprised by how quickly the Nos added up, especially given there were numerous paper reviews and small asks that I also said no to throughout the year not captured here. Most of the items on the list were in fact small. However, I also didn’t volunteer for several events that would have taken whole days out of my year. I also removed myself as a co-PI of a NSF grant that I didn’t feel I could adequately contribute to given professional and personal responsibilities. I really struggled with this decision, but it felt like the only fair option for everyone involved. My collaborators on the grant were very supportive of me.

My No list was inspired partially by an article in Nature. In the piece, four scientists formed a “no committee” where they challenged themselves to make a no list and hold one another accountable.

I am proud of saying no more. However, the no list also hides the sheer number of things I said yes to in 2024. I was rejigging two courses, onboarding new members of the lab, and I had taken on a new leadership role. I loved every aspect of the work, but something still felt off. Thus, I ended the Fall semester feeling a bit rattled. I knew something wasn’t working for me.

In January, I began my trip to Japan after the Fall semester and the holidays. My partner and I first spent a week traveling between Tokyo, Kyoto, and Hiroshima. In each city, there was a mix of temples and shrines right alongside modern skyscrapers. On the same street you could find a traditional bath house and a Starbucks.

We ate at McDonalds. We ate at izakayas (an informal Japanese gastropub). We ate traditional Japanese meals. We purchased gifts from big box stores and also artisan markets. Through all of these experiences, there was one constant thread—a richness of intentionality. From the train conductors to chefs to sanitation workers, it was hard not to observe an enormous sense of pride in one’s work.

I think these ideas are captured well by the Japanese word ikigai (生き甲斐) which roughly translates to “a reason for being”. It represents a highly intentional approach to work, relationships, and personal fulfillment.

One of Japan’s most well-known recent exports is Marie Kondo, popularized in a Netflix series where she helps Americans declutter their homes using her KonMari method. She takes clients through the process of systematically simplyfing and tidying their homes with intentionality. Kondo sums up her philosophy by noting, “The true purpose is to find and keep the things you truly love”.

Ideas of intentionality and simplicity connect well with two of Cal Newport’s core messages in Slow Productity, which is to Do Fewer Things and Obsess over Quality.

Thus, throughout my trip to Japan and since returning home, I’ve tried connecting Kondo’s ideas and other aspects of Japanese culture to my life, both professionally and personally (including cleaning out my closets). I am now focused on tidying my work life.

There is of course actual decluttering I can undertake in my inbox or in my office. I aim to go deeper while also recognizing it won’t be a quick or easy process. Beyond saying no to a handful of requests as I did in 2024, I want to connect deeply with what brings me joy in work. I have a lot to process, but this is my current focus. I want to be laser focused on what is essential. My only goal for 2025 is to do less things. I’m actually fairly happy with the overall amount that I work, but I want to do less different things. I’m dedicating some serious time to consider what I should stop doing. To paraphrase Michelangelo, I want to examine the marble and carve away what is essential.

I’d love to hear from others as I work through this process. Do you feel pulled in a million directions? How do you think about what to work on next? How do you say no?

Here are several books that I inspire me.

Love the "no list" idea! And what a reflective Japan trip, sounds like you had a good time!!

This isn't a big problem for me yet, but I have trouble saying "no" on the spot. I like to wait and see whether I see a big enough upside in a request. But this leads to another problem: If I don't see an upside and respond quickly, I procrastinate responding for weeks, feeling guilty the whole time. (these are folks I've never met, not friends/colleagues btw).

I expect I'll need much more compartmentalization of my time to make the next few years work, but absent hard deadlines, I've often struggled to force my brain onto a topic at a specific time (more so if there's low reward for me and my colleagues).