Optimal size and structure of research labs

I started my lab group just over two years ago. The lab grew organically as students entered the lab, I adopted some other mentees, and I hired my first postdoc. I didn’t have an ideal lab size or structure when I started. I think this is common among new lab leaders. In discussing with other faculty, the only decision seems to be a “small lab” or “big lab”. I wanted to dive into these ideas more to ask, what is the ideal lab size and composition?

In STEM fields, lab groups can vary enormously in size and structure. A lot of the variation can be explained by different types of universities. At universities with very high research activity (R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity), lab groups may have research scientists, postdoctoral fellows, PhD and MS students, and undergraduates. At other institutions, it might be common only to have MS students and undergraduates. At Primarily Undergraduate Institutions (PUIs), labs may consist almost entirely of undergraduate researchers.

Here, I’ll focus on larger colleges or universities where a mix of postdoctoral and graduate students is common. Non-academics may be surprised at the enormous variation of lab groups within single universities, or even within individual departments. What is the optimal size, and composition, for a lab to be productive?

In my experience at several universities, I have seen a lot of variation in lab groups. I have seen lab groups that consist of just the PI and an occasional graduate student to large enterprises with a PI, ten postdocs, a few dozen graduate students, and a hoard of undergraduates. Across this spectrum, I have seen productive labs. Naturally, with a large lab, there might be more papers produced per year and more grant money being brought in to support so many people1. Yet, I have also seen small labs that produce a lot, especially as PIs in these small labs have more time to do science themselves.

Let’s turn to the literature for data on how to build a lab.

A 2015 study2 examined several decades of productivity data from a single biology department in the USA. Over the time span, there were 119 principal investigators and 5,694 individual lab members.

The authors of the study then examined what variables might be correlated with lab productivity, which was the number of publications per year. On average, each lab produced 5.3 publications per year, but this number varied tremendously. The authors note, “For the average-sized laboratory, adding one additional member is correlated with an increase in the number of a laboratory’s publications by 0.24”. However, each additional postdoc added 0.31 publications per year whereas a graduate student added 0.14 publications per year. They also found that productivity gains from adding new lab members diminished for labs with over 25 members.

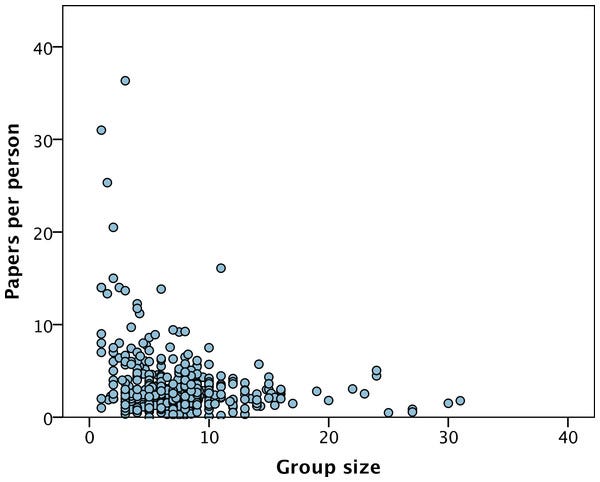

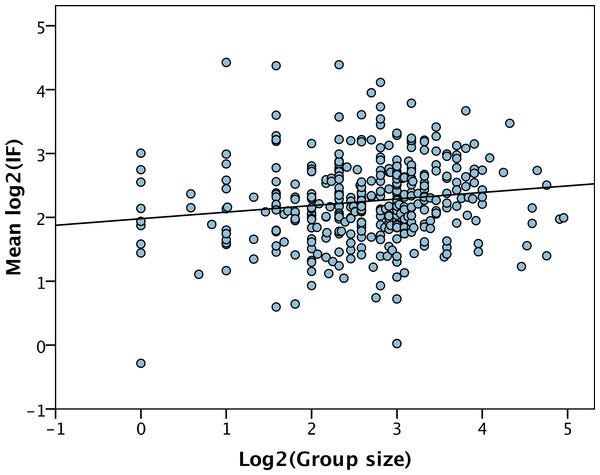

In another 2015 study3, authors examined productivity (publications, journal impact factor, and the number of citations) data from nearly 400 life science laboratories in the United Kingdom. They found that the number of publications produced by each lab was correlated with lab size, but this only explained 20% of the variability in publications.

As with the previous study, postdocs contributed more to productivity than graduate students. Each postdoc added 3.48 papers per five years, whereas PhD students added 1.53. The impact factor of journals where the work was published also increased with group size, but the effect size was small. The pattern was similar for the number of citations.

Because of the diminishing returns of adding more group members, the authors argue that funding agencies should favor smaller research groups. As a corollary, given the relative costs and effects on productivity, they argued it would be better to invest in hiring more PIs than more postdocs and PhD students.

Let’s return to a modified version of our original question. From the perspective of the PI, what is the optimal lab size and composition? This question is, of course, only relevant in situations where a PI has some flexibility (in terms of funding or institutional norms) in how to build their lab. It is clear that larger groups will produce more work. However, there are diminishing returns when lab groups grow too large. I think the above papers provide some useful data in terms of productivity differences between types of lab members. However, I think the papers aren’t able to capture two important dynamics. First, I think a PI should evaluate their own strengths and weaknesses in reflecting on what type of lab they want to build. For a PI that wants to be in the lab or field every day, they are going to have a smaller lab. For a PI skilled in the management side of running a small organization, it might be okay to build a larger lab. Second, I think the specific composition of a lab may also matter a lot. A lab with a lot of graduate or undergraduate students may not have enough overall mentorship. Instead, a lab with several research scientists and postdocs may be able to supplement mentoring4 by the principal investigator.

So, what is the optimal size and composition of a research lab? I think it depends. It is clear that certain types of lab members will be more productive than others, but the overall success of a lab will depend on the individuals in the lab, the PI, and institutional support.

What do you think is the ideal size and composition of a university laboratory? Do you know of similar studies on the topic? Please share below.

https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq7056

http://www-2.rotman.utoronto.ca/facbios/file/Bringing_Labs_Back_In_RP_2015.pdf

https://peerj.com/articles/989/

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1912488116